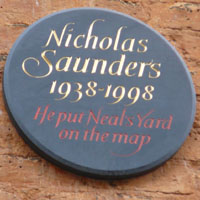

While Neal’s Yard owes its name to Thomas Neale, who received a piece of land in 1690 from William III and created the Seven Dials area in which Neal’s Yard is situated, it was Nicholas Saunders who put Neal’s Yard on the map.

While Neal’s Yard owes its name to Thomas Neale, who received a piece of land in 1690 from William III and created the Seven Dials area in which Neal’s Yard is situated, it was Nicholas Saunders who put Neal’s Yard on the map.

Until the mid-1970s, Neal’s Yard did not appear on the London A to Z. In 1976 Nicholas started the Whole Food Warehouse, which was the beginning of a big change for Neal’s Yard. Up until then it had been a dark, rat infested, derelict yard with a few warehouses that supported the Covent Garden fruit and veg market. Through Nicholas Saunders’ entrepreneurial skills Neal’s Yard turned into the thriving, exciting alternative place for which it is known today.

These are his own words written in the mid-1980s:

“I spent the early 70s producing alternative guidebooks, ending with Alternative England and Wales, which I researched by travelling around the country in a large van converted into an office/bedsit. By the summer of 1975 the book was finished and I spent most of the next year in Christiania, a large community in Denmark. Every few weeks I would travel back to London with my living van and take back to Christiania a load of nuts, beans and other wholefoods which were so much cheaper here that they paid for the trip. And that is how I got involved with selling wholefoods.

A few years before, I had been looking for somewhere to live in the run down parts of Soho and Covent Garden and was amazed to find 2 Neal’s Yard for sale at £7,000 – the snag being that it was let for next to nothing and the area was scheduled for redevelopment. But the lease was nearly finished and I thought that, by living there, I could help save the area from demolition. In fact I was refused planning permission to live there, but later when I was in Christiania the tenants moved out and I had to find some use for the building.

A few years before, I had been looking for somewhere to live in the run down parts of Soho and Covent Garden and was amazed to find 2 Neal’s Yard for sale at £7,000 – the snag being that it was let for next to nothing and the area was scheduled for redevelopment. But the lease was nearly finished and I thought that, by living there, I could help save the area from demolition. In fact I was refused planning permission to live there, but later when I was in Christiania the tenants moved out and I had to find some use for the building.

I decided to start a wholefood shop which I would like myself – one that was cheap, efficient and would not make customers feel bad because they could not recognise a mung bean. At that time wholefood shops were mostly of the hippy style – folksy looking with open sacks and used paper bags; nice meeting places for the in-groups but hopelessly inefficient, expensive and tending to make ordinary people feel like intruders.

I went to the planning department and outlined my idea. The officer’s response was: “I’m quite sure the committee would refuse permission, as they are against high profit businesses moving in”. I was amazed by the remark and thought she had misheard until I realised that this was her way of saying “Get lost” – they had already prevented me living here and now they wanted to keep me out altogether. That made me angry and I consulted my solicitor who said that I could legally start the shop without planning permission and if I got support from the neighbours, then I would stand a good chance of getting permission in the end.

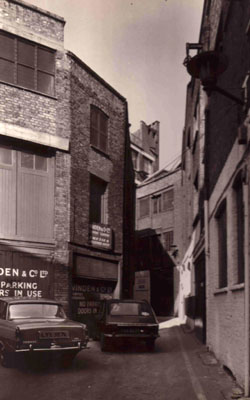

Perhaps it was the challenge I needed, as everyone said it was a crazy place to start a food shop. At that time the buildings looked derelict with windows broken or boarded up. Neal’s Yard was a filthy backyard over-run by rats and used by tramps as a lavatory. It was hard to find and was not even on the A to Z.

Perhaps it was the challenge I needed, as everyone said it was a crazy place to start a food shop. At that time the buildings looked derelict with windows broken or boarded up. Neal’s Yard was a filthy backyard over-run by rats and used by tramps as a lavatory. It was hard to find and was not even on the A to Z.

My plan was just to get the shop started, then leave it to an old friend Judith to run, as my long term plan was to go off and set up a village community based on the lessons I had learned through living in Christiania. I started converting the building with amateur help, and after a hard day’s work would come home tired to my flat in the World’s End to find half a dozen people sitting around – unusual people and inspiring conversations maybe, but now I was not coming back till I had finished the shop. That very night the phone rang and Alan told me there was such a serious fire they’d had to abandon the flat, and by the time I got there my home was burned to the ground. I went out to where my friends were huddled. Ebba explained how she had been meditating in front of a candle and had knocked it over. I told her that the whole flat represented the life I wanted to leave behind and that it was the best thing she could have done for me. But my reaction was so unexpected that poor Ebba collapsed onto the pavement.

After three months work the shop was finished and it opened on November 11976. Although it was fitted out very cheaply in Christiania style using materials from demolition sites, it looked refreshingly original and simple – heavy shelves loaded with large clear plastic bags full of beans of various colours with the price written on by hand.

All the food was packed on the first floor and was hoisted up on the human counterweight principle – one person would attach the load, a second would jump out of the window holding the rope coming down from the pulley, while the third would haul in the load. It was hard work, but an exhilarating exercise in trust and awareness. All sorts of things could go wrong, for instance if the load was too heavy you would be left suspended or you could collide with he load in mid air. Yet there was only one accident in perhaps 10,000 jumps – when Tara was showing off to an admirer. The packing was done by hand by three people working together: the food was shovelled into bags, weighed, marked and then sent down an indoor chute to the shop. I made a packing trough and other equipment, arranged so that three people could chat as they worked together and positioned so as to give them an unobstructed view all around and out of the windows – ‘like working on the bridge of a ship’, one said.

All the food was packed on the first floor and was hoisted up on the human counterweight principle – one person would attach the load, a second would jump out of the window holding the rope coming down from the pulley, while the third would haul in the load. It was hard work, but an exhilarating exercise in trust and awareness. All sorts of things could go wrong, for instance if the load was too heavy you would be left suspended or you could collide with he load in mid air. Yet there was only one accident in perhaps 10,000 jumps – when Tara was showing off to an admirer. The packing was done by hand by three people working together: the food was shovelled into bags, weighed, marked and then sent down an indoor chute to the shop. I made a packing trough and other equipment, arranged so that three people could chat as they worked together and positioned so as to give them an unobstructed view all around and out of the windows – ‘like working on the bridge of a ship’, one said.

I invented a pricing system which reflected the work we put in, instead of a percentage mark-up. I put on a charge for weight to reflect the cost of collecting and hauling upstairs, another for packing which increased with stickiness, and a constant selling charge. The result was that our prices were lower than anywhere else except in small sizes of sticky goods and very much lower for large sizes of things like nuts which were expensive and easy to pack. So we filled a gap by offering by far the cheapest goods in the sizes between retail and wholesale – ideal for ‘food co-ops’ and informal groups of people who bought in bulk to save money.

After we opened I worked out a system for selling good cheap honey in 7lb jars. We collected the 660lb honey drums from Oxford on our truck, warmed them ( in a special cupboard I had made under the stairs ) until the honey was runny enough to pour and then we would mix in some crystalline honey to make it set in the jars. After the shop closed, we rolled the drums up onto the counter where we screwed on giant taps. We had to collect a pallet load of 320 7lb jars from Greenwich and as there was no storage space, the operation required careful coordination. That was a success and was soon followed by 7lb jars for tahini, vegetable oils, cider vinegar and peanut butter. I did a tour of old machinery dealers with a bag of roasted peanuts and after trying all sorts of machines (including a waste disposer) found that a grinder once used for making face cream produced the perfect peanut butter, a combination of crunchy chips and creamy texture.

After we opened I worked out a system for selling good cheap honey in 7lb jars. We collected the 660lb honey drums from Oxford on our truck, warmed them ( in a special cupboard I had made under the stairs ) until the honey was runny enough to pour and then we would mix in some crystalline honey to make it set in the jars. After the shop closed, we rolled the drums up onto the counter where we screwed on giant taps. We had to collect a pallet load of 320 7lb jars from Greenwich and as there was no storage space, the operation required careful coordination. That was a success and was soon followed by 7lb jars for tahini, vegetable oils, cider vinegar and peanut butter. I did a tour of old machinery dealers with a bag of roasted peanuts and after trying all sorts of machines (including a waste disposer) found that a grinder once used for making face cream produced the perfect peanut butter, a combination of crunchy chips and creamy texture.

I set a target that I would take a break when our turnover reached £ 1,000 a day and that took less than four months. We were cheaper then everywhere else and incredibly busy – in fact, we not only undercut Sainsburys on comparable items but our turnover was double theirs per square foot, according to their own ads. There was no trick to our success, we were simply the best wholefood shop. We were cheap and reliably well stocked and there were samples for tasting. The descriptions were straightforward without claims and all the prices per pound were worked out. There were no come-ons or other enticements to buy. Service was efficient but not subservient – my directive was that staff should help shy customers but not to give way to the demands of rude or pushy people, in fact we used to be equally rude back, to their surprise.

However we did not despise our customers. It was more that we regarded them as no better than ourselves and we had more experience of wholefoods. The staff were all customers who had asked for a job and a community feeling developed that included both us and them equally. This set the style of the place. We also allowed a little teasing such as on the first of April we would put a plastic fly in every bag of muesli.

However we did not despise our customers. It was more that we regarded them as no better than ourselves and we had more experience of wholefoods. The staff were all customers who had asked for a job and a community feeling developed that included both us and them equally. This set the style of the place. We also allowed a little teasing such as on the first of April we would put a plastic fly in every bag of muesli.

Now that I was satisfied with what we offered, I tuned my attention towards the organisation. I was keen on doing things in ways which would provide a balance between low cost, efficiency and a high quality of life. My ideas were influenced by Gurdjieff – that fulfillment does not come from making work effortless, but by doing work which is demanding, so long as it gives opportunity for variety, learning and responsibility. I was in favour of physical work and against labour saving methods that created mindless jobs, noise or isolation. Why operate a machine all day, then go home and do exercises when you could be getting exercise doing the work yourself?

So jobs were rotated, from cleaning to dealing with the money and I used to encourage responsibility by giving workers turns at managing the business with authority to sign cheques – often without even knowing their surnames, which shocked the bank manager. The atmosphere was one of high energy, with no nonsense and attracted an enthusiastic lot of workers. The business soon started to make a lot of money too and after 9 months I divided up the profits among the workers and reduced the prices still further.

However, it was not all roses and as the number of staff increased and the work became more routine, the attitude gradually changed – particularly when we got so busy we worked two shifts a day. The most adventurous people got bored and moved on – which I thought was a good thing: they had an unusual opportunity to learn how to run a successful small business and could go out and use what they had learned. But the new staff did not like being told to be aware what needed doing, they wanted to be told what to do as in a more conventional set-up. This put Judith in a difficult position as manager and when she left to become a carpet restorer, I began to feel more and more The Boss, which I hated. Yet, of course, I wanted to see my standards kept up.

The work-credit system

I thought up various structures that would solve the problem and eventually thought that I had come up with a solution not only for us, but one that was fundamentally so good it could revolutionise the business world. It was a self-adjusting system based on work credits, incorporating feedback from both workers and customers. It would be intrinsically fair, as the value of each person’s contribution would be, in effect, auctioned against other people able to offer the same contribution – weather the input be work, responsibility or risking capital – without any external authority making assessments.

The first stage was to award credit points to each job according to its worth as judged by the workers. This was to be done by allowing workers to chose their jobs, then giving more credits to the last jobs chosen until eventually a balance was reached. The result, I hoped, would be that everyone could work at their own pace and be fairly paid for what they achieved. And the type who rushed around getting exhausted but got very little done would have to learn how to be more productive or they would simply find they did not earn enough and leave – all without the boss having to be bossy. I would feel more at ease and could concentrate on quality control as I used to.

So much for the theory. In practice, the workers rejected the scheme outright as seeming too much like piecework and because they felt it would go against the group spirit. However, that stimulated ideas and I adopted a system developed from a suggestion by one of the workers, Michael Loftus: the worker were divided into two shifts working three days each, with a ‘duty manager’ working for two weeks to provide continuity. The effect was that each person had to get a lot more work done, sometimes working 12 hours a day, but earned as much in three days as they used to in a week. And, although the scheme fell short of my ambitious aims, it did make for teamwork and provided me with a reliable basis for costing, as the total wages were a strict proportion of the takings.

The vertical garden

The vertical garden

. . .That seemed to be the end of my scope as there were no more empty buildings. I also wanted to do other things and spent some time designing some plant pots for the Yard which I made in a friend’s workshop in Wales. They are like interlocking hollow bricks which stack up t form a self supporting wall, leaving an air space between them and the building behind, to avoid spreading damp. They only project a foot, so provide a kind of vertical garden without wasting ground space.

The holiday

I decided that I would leave with a bang. I invited everyone from the yard to the Canary Islands for a winter holiday in Lanzarote – 55 people in all, including some from Food for Thought, who were our best customers, and from Community, our best suppliers. I gave everyone a sort of ‘treasure island’ kit consisting of a map, a torch, a toy sunshade, a few sweets and a wallet containing real Spanish money. We took on the plane a marquee big enough for everyone to sleep in and we camped on the beach for a week.

Conclusion

The Yard has developed into a social scene. Even thought he businesses are each independent, everyone who works in them, and many of the regular customers, identify with the place. In fact most of the workers are customers who had asked for a job. My old idea of a village community has manifested in the form of a community of small businesses, each one individual and free to go its own way. It is rather like a family, with me as a father and the businesses as my grown-up children. They generally get on well and help one another, but there have also been bitter disputes. Nearly every one has rebelled against me, or my laid down principles, at some stage just like adolescents – and it has bee a painful experience. Yet they have mainly kept to the spirit of my ideas, and provide really good jobs which are well paid and involve responsibility. They Yard has also become the meeting place of a social group based on the sort of people who work there. many friendships have formed with several leading to marriage – the most dramatic being when Anita of the Coffee House married Randolph of the Dairy. They held a sit down feast for everyone in the Yard – and symbolised their union by serving coffee ice-cream.

Pingback: Kenny’s muesli « considerthesauce.net

Pingback: Shoplog – De Tuinen | Ongevera

Pingback: Shoplog - De Tuinen : Ongevera

Pingback: Life in the Big Smoke | Can you cross the street?

Pingback: Neal’s Yard, une oasis colorée en plein cœur de Londres. | Le Blog Bio

Pingback: Theatre & Barge Boats in London | the travelling wine glass

Pingback: Ocho lugares que visitar en Londres que (casi) nadie conoce... ¡y gratis! - MujerTrend

Pingback: Neal's Yard - Twenty Thousand London Streets

Pingback: Alternative England and Wales (1975) – the psychedelic guide to UK counterculture – edible woman

Pingback: Things you will love about Covent Garden - Citybase Apartments

Pingback: Spending a Day in London - Alex & Yula's travels

Pingback: Neal's Yard: Colourful Corner Of Covent Garden Full Of Shops And Cafes

Pingback: Where seven streets meet | yamey

Pingback: Here’s What’s Hidden Away In This Colourful Corner Of Covent Garden • Neal’s Yard - What's On In City of London

Pingback: Hidden Gems in London – 6 of The Most Vibrant Places You Will Never Forget - Mature & Thriving

Pingback: नीलस् यार्ड – Vanilla affidavit site

Pingback: Neal’s Yard: The One Man Wonder | Understanding Cities and Spatial Cultures

Pingback: Hippy, capitalist, guru, grocer: the forgotten genius who changed British food – Heathlinecare.com.ng

Pingback: Hippy, capitalist, guru, grocer: the forgotten genius who changed British food | Food - Heart To Heart

Pingback: Hippy, capitalist, guru, grocer: the forgotten genius who changed British food | Food – FoodIndustryNetwork

Pingback: Hippy, capitalist, guru, grocer: the forgotten genius who changed British food | Food – GreenEarn Sports

Pingback: Hippy, capitalist, guru, grocer: the forgotten genius who changed British food | Food - News Leaflets

Pingback: Hippy, capitalist, guru, grocer: the forgotten genius who modified British meals | Liliana News

Pingback: Hippy, capitalist, guru, grocer: the forgotten genius who changed British food | Food - SecularTimes

Pingback: Hippy, capitalist, guru, grocer: the forgotten genius who changed British food | Food | Skeptic Society Magazine

Pingback: Hippy, capitalist, guru, grocer: the forgotten genius who changed British food | Food - YoursBulletin

Pingback: Hippy, capitalist, guru, grocer: the forgotten genius who changed British food | Food - SwiftTelecast

Pingback: Hippy, capitalist, guru, grocer: the forgotten genius who changed British food | Food - NewsContinue

Pingback: Hippy, capitalist, guru, grocer: the forgotten genius who changed British food | Food - NewsConcerns

Pingback: Hippy, capitalist, guru, grocer: Nicholas Saunders and “Various London” | News Lexa

Pingback: Hippy, capitalist, guru, grocer: the forgotten genius who changed British food | Food - Illuminati Press